Populations of Concern

Key Findings

Key Finding 1: Vulnerability Varies Over Time and Is Place-Specific

Key Finding 1: Across the United States, people and communities differ in their exposures, their inherent

Key Finding 2: Health Impacts Vary with Age and Life Stage

People experience different inherent sensitivities to the impacts of

Key Finding 3: Social Determinants of Health Interact with Climate Factors to Affect Health Risks

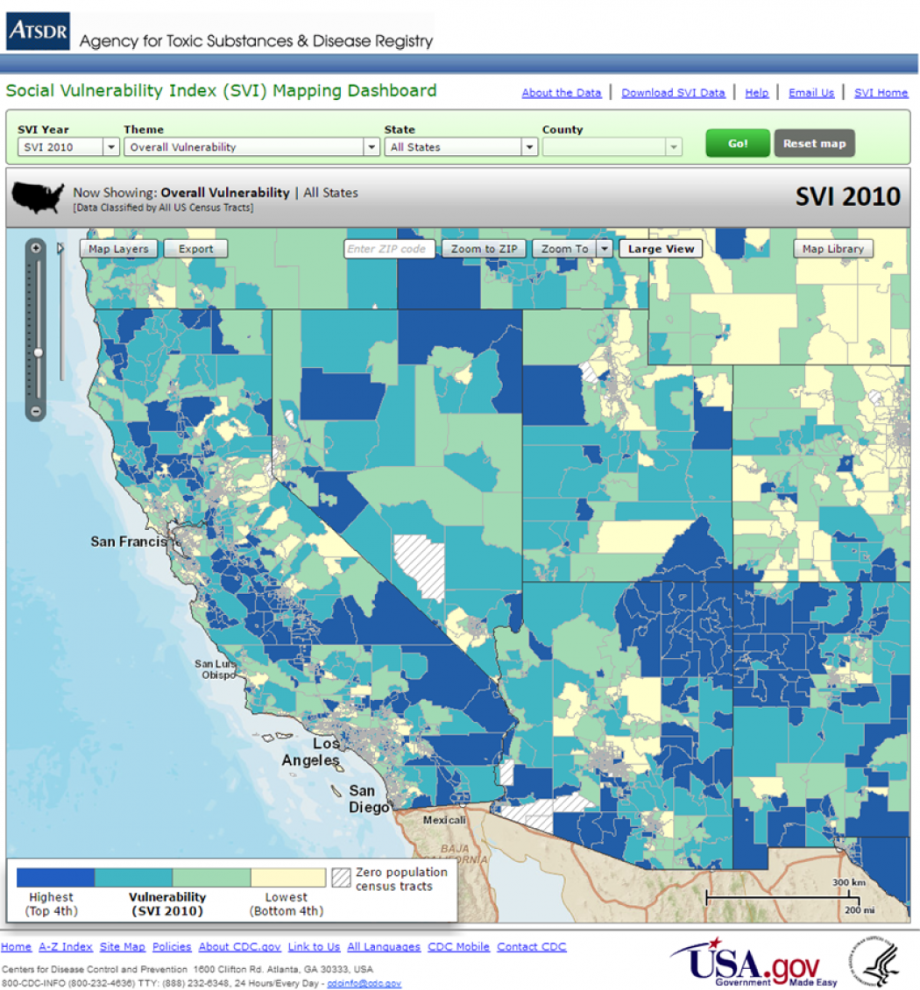

Key Finding 4: Mapping Tools and Vulnerability Indices Identify Climate Health Risks

The use of geographic data and tools allows for more sophisticated mapping of

Food is distributed to people in need at Catholic Community Service in Wheaton, MD, November 23, 2010.

© Brooks Kraft/Corbis

Some groups face a number of stressors related to both climate and non-climate factors. For example, people living in impoverished urban or isolated rural areas, floodplains, coastlines, and other at-risk locations are more vulnerable not only to extreme weather and persistent climate change but also to social and economic stressors. Many of these stressors can occur simultaneously or consecutively. Over time, this “accumulation” of multiple, complex stressors is expected to become more evident1 as climate impacts interact with stressors associated with existing mental and physical health conditions and with other

Some

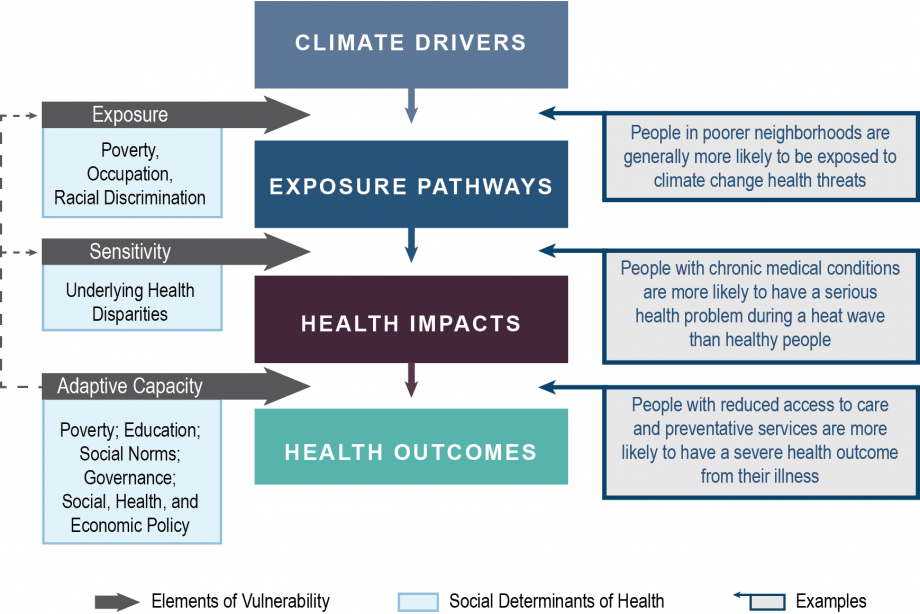

Figure 9.1: Determinants of Vulnerability

-

Vulnerability is the tendency or predisposition to be adversely affected by climate-related health effects, and encompasses three elements: exposure, sensitivity or susceptibility to harm, and the capacity to adapt to or to cope with change. Exposure is contact between a person and one or more biological, chemical, or physical stressors, including stressors affected by climate change. Contact may occur in a single instance or repeatedly over time, and may occur in one location or over a wider geographic area. Sensitivity is the degree to which people or communities are affected, either adversely or beneficially, by climate variability and change. Adaptive capacity is the ability of communities, institutions, or people to adjust to potential hazards, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences. A related term,

resilience , is the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events. People and communities with strong adaptive capacity have greater resilience. - Risk is the potential for consequences to develop where something of value (such as human health) is at stake and where the outcome is uncertain. Risk is often represented as the probability of the occurrence of a hazardous event multiplied by the expected severity of the impacts of that event.

- Stressors are events or trends, whether related to climate change or other factors, that increase vulnerability to health effects.

Figure 9.2: Intersection of Social Determinants of Health and Vulnerability

VIEW

People or communities can have greater or lesser vulnerability to health risks depending on social, political, and economic factors that are collectively known as social determinants of health.4 Some groups are disproportionately disadvantaged by social determinants of health that limit resources and opportunities for health-promoting behaviors and conditions of daily life, such as living/working circumstances and access to healthcare services.4 In disadvantaged groups, social determinants of health interact with the three elements of vulnerability by contributing to increased exposure, increased sensitivity, and reduced adaptive capacity (Figure 9.2). Health risks and vulnerability may increase in locations or instances where combinations of social determinants of health that amplify health threats occur simultaneously or close in time or space.5,6 For example, people with limited economic resources living in areas with deteriorating

Factors that Contribute to Exposure

Exposures to climate-related variability and change are determined by a range of factors that individually and collectively shape the nature and extent of exposures. These factors include:

- Occupation: Certain occupations have a greater risk of exposure to climate impacts. People working outdoors or performing duties that expose them to extreme weather, such as emergency responders, utility repair crews, farm workers, construction workers, and other outdoor laborers, are at particular risk.10

-

Time spent in risk-prone locations: Where a person lives, goes to school, works, or spends leisure time will contribute to exposure. Locations with greater health threats include urban areas (due to, for example, the “heat island” effect or air quality concerns), areas where airborne allergens and other air pollutants occur at levels that aggravate

respiratory illnesses, communities experiencing depleted water supplies or vulnerable energy and transportation infrastructure, coastal and other flood-prone areas, and locations affected bydrought andwildfire .11,12,13 - Responses to extreme events: A person’s ability or, in some cases, their choice whether to evacuate or shelter-in-place in response to an extreme event such as a hurricane, flood, or wildfire affects their exposure to health threats. Low-income populations are generally less likely to evacuate in response to a warning (see Ch. 4: Extreme Events).7

-

Socioeconomic status: Persons living in poverty are more likely to be exposed to extreme heat and air pollution.14,15 Poverty also determines, at least in part, how people perceive the risks to which they are exposed, how they respond to evacuation orders and other emergency warnings, and their ability to evacuate or relocate to a less risk-prone location (see Ch. 8: Mental Health).7 - Infrastructure condition and access: Older buildings may expose occupants to increased indoor air pollutants and mold, stagnant airflow, or high indoor temperatures (see Ch. 3: Air Quality Impacts). Persons preparing for or responding to flooding, wildfires, or other weather-related emergencies may be hampered by disruption to transportation, utilities, medical, or communication infrastructure. Lack of access to these resources, in either urban or rural settings, can increase a person’s vulnerability (see Ch. 4: Extreme Events).16,17

-

Compromised mobility,

cognitive function, and other mental or behavioral factors: These factors can lead to increased exposure to climate-related health impacts if people are not aware of health threats or are unable to take actions to avoid, limit, or respond to risks.18 People with access and functional needs may be particularly at risk if these factors interfere with their ability to access or receive medical care before, during, or after a disaster or emergency.

Characterizing Biological Sensitivity

The sensitivity of human communities and individuals to climate change stressors is determined, at least in part, by biological traits. Among those traits are the overall health status, age, and life stage. From fetus, to infant, to toddler, to child, to adolescent, to adult, to the elderly, persons at every life stage have varying sensitivity to climate change impacts.11,19,20 For instance, the relatively immature immune systems of very young children make them more sensitive to aeroallergen exposure (such as airborne pollens). In addition to life stage, people experiencing long-term

Adaptive Capacity and Response to Climate Change

Many of the same factors that contribute to exposure or sensitivity also influence the ability of both individuals and communities to adapt to climate variability and change. Socioeconomic status, the condition and accessibility of infrastructure, the accessibility of health care, certain

Communities of Color, Low Income, Immigrants, and Limited English Proficiency Groups

Nursing students and faculty at Emory University School of Nursing in Atlanta, Georgia volunteering to give checkups in migrant workers’ camps, June 12, 2006.

© Karen Kasmauski/ Corbis

In the United States, some communities of color, low-income groups, people with limited English proficiency (

The number of people of color in the United States who may be affected by heightened vulnerability to climate-related health risks will continue to grow. Currently, Hispanics or Latinos, Blacks or African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans, and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders represent 37% of the total U.S. population.47,48 By 2042, they are projected to become the majority.49 People of color already constitute the majority in four states (California, Hawaii, New Mexico, and Texas) and in many cities.48 Numbers of LEP and undocumented immigrant populations have also increased. In 2011, LEP groups comprised approximately 9% (25.3 million individuals) of the U.S. population aged five and older.50 In 2010, approximately 11.2 million people in the United States were undocumented.51

Vulnerability to Climate-Related Health Stressors

Key climate impacts for some communities of color and low-income, LEP, and immigrant populations include heat waves, other extreme

Race is an important factor in vulnerability to climate-related stress, but it can be difficult to isolate the role of race from other related socioeconomic and geographic factors. Some racial minorities are also members of low-income groups, immigrants, and people with limited English proficiency, and it is their socioeconomic status (

Extreme heat events. Some communities of color and some low-income, homeless, and immigrant populations are more exposed to heat waves,55,56 as these groups often reside in urban areas affected by heat island effects.12,14,24,57 In addition, these populations are likely to have limited

Other weather extremes. As observed during and after Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane/Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy, some communities of color and low-income people experienced increased illness or injury, death, or displacement due to poor-quality housing, lack of access to emergency communications, lack of access to transportation, inadequate access to health care services and medications, limited post-disaster employment, and limited or no health and property insurance.61,62,63,64,65,66 Following a 2006 flood in El Paso, Texas, Hispanic ethnicity was identified as a significant risk factor for adverse health effects after controlling for other important socioeconomic factors (for example, age and housing quality).67 Adaptation measures to address these risk factors—such as providing transportation during evacuations or targeted employment assistance during the recovery phase—may help reduce or eliminate these health impact disparities, but may not be readily available or affordable (see also Ch. 4: Extreme Events).61,62,63,65,66

Degraded air quality. Climate change impacts on outdoor air quality will increase exposure in urban areas where large proportions of minority, low-income, homeless, and immigrant populations reside. Fine

Waterborne and vector-borne diseases. Climate change is expected to increase exposure to waterborne pathogens that cause a variety of illnesses—most commonly

Food safety and security. Climate change affects food safety and is projected to reduce the nutrient and protein content of some crops, like wheat and rice. Some communities of color and low-income populations are more likely to be affected because they spend a relatively larger portion of their household income on food compared to more affluent households. These groups often suffer from poor-quality diets and limited access to full-service grocery stores that offer healthy and affordable dietary choices (see also Ch. 7: Food Safety).36,37,85,86

Psychological stress. Some communities of color, low-income populations, immigrants, and LEP groups are more likely to experience stress-related mental health impacts, particularly during and after extreme events. Other contributing factors include barriers in accessing and affording mental health care, such as counseling in native languages, and the availability and affordability of appropriate medications (see also Ch. 8: Mental Health).87,88

Indigenous Peoples in the United States

A number of health risks are higher among Indigenous populations, such as poor mental health related to historical or personal

Food safety and security. Examples of how climate changes can affect the health of Indigenous peoples include changes in the abundance and nutrient content of certain foodstuffs, such as berries for Alaska Native communities;106 declining moose populations in Minnesota, which are significant to many Ojibwe peoples and an important source of dietary protein;107,108 rising temperatures and lack of available water for farming among Navajo people;109 and declines in traditional rice harvests among the Ojibwe in the Upper Great Lakes region.110 Traditional foods and livelihoods are embedded in Indigenous cultural beliefs and subsistence practices.111,112,113,114,115,116,117 Climate impacts on traditional foods may result in poor nutrition and increased

Changes in aquatic habitats and species also affect subsistence fishing.119 Rising temperatures affect water quality and availability. Lower oxygen levels in freshwater and seawater degrade water quality and promote the growth of disease-causing

Indigenous deckhand pulls in net of geoducks near Suquamish, Washington, January 17, 2007. Traditional foods and livelihoods are embedded in Indigenous cultural beliefs and subsistence practices.

© Mike Kane/Aurora Photos/ Corbis

Water security. Indigenous peoples may lack access to water resources and to adequate infrastructure for water treatment and supply. A significant number of Indigenous persons living on remote reservations lack indoor plumbing and rely on unregulated water supplies that are vulnerable to

Loss of cultural identity. Climate change threatens sacred ceremonial and cultural practices through changing the availability of culturally relevant plant and animal species.95,130 Climate-related threats may compound historical impacts associated with colonialism, as well as current effects on tribal culture as more young people leave reservations for education and employment opportunities. Loss of tribal territory and disruption of cultural resources and traditional ways of life131,132 lead to loss of cultural identity.133,134,135 The loss of medicinal plants due to climate change may leave ceremonial and traditional practitioners without the resources they need to practice traditional healing.114,136 The relocation of young people may reduce interactions across generations and undermine the sharing of traditional knowledge, tribal lore, and oral history.137,138

Degraded infrastructure and other impacts. Rising temperatures may damage transportation infrastructure on tribal lands. Changing ice or thawing permafrost, flooding, and drought-related dust storms may block roads and cut off communities from access to evacuation routes and emergency medical care or social services.139 Poor air quality from blowing dust affects southwestern Indigenous communities, particularly in Arizona and New Mexico, and is likely to worsen with drought conditions.140 Exposure to impaired air quality also affects Indigenous communities, especially those downwind from urban areas or industrial complexes.

Children and Pregnant Women

© JGI/Tom Grill/Blend Images/ Corbis

Children are vulnerable to adverse health effects associated with environmental exposures due to factors related to their immature physiology and metabolism, their unique exposure pathways, their biological sensitivities, and limits to their adaptive capacity. Children pass through a series of windows of vulnerability that begin in the womb and continue through their second decade of life. Children have a proportionately higher intake of air, food, and water relative to their body weight compared to adults.19 They also share unique behaviors and interactions with their environment that may increase their exposure to environmental contaminants. For example, small children often play indoors on the floor or outdoors on the ground and place hands and other objects in their mouths, increasing their exposure to dust and other contaminants, such as pesticides, mold spores, and allergens.141 There is, however, large variation in vulnerability among children at different life stages due to differing physiology and behaviors (Figure 9.3). Climate change—interacting with factors such as economic status, diet, living situation, and stage of development—will increase children’s exposure to health threats.11,20,142,143,144 The impact of poverty on children’s health is a critical factor to consider in ascertaining how climate change will be manifest in children. Poor and low-income households have difficulty accessing health care and meeting the basic needs that are crucial for healthy child development. In addition, children in poverty are less likely to have access to air conditioning to mitigate the effects of extreme heat. Children living in poverty are also less likely to be able to respond to or escape from extreme weather events.11,20,142,143,144

Figure 9.3: Vulnerability to the Health Impacts of Climate Change at Different Life Stages

Vulnerability to Climate-Related Health Stressors

Extreme heat events. An increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events (see Ch. 2: Temperature-Related Death and Illness) will affect children who spend time outdoors or in non-climate-controlled indoor settings. Student athletes and other children who are susceptible to heat-related illnesses when they exercise or play outdoors in hot and humid weather may be poorly acclimated to physical exertion in the heat. Some 9,000 high school athletes in the United States are treated for exertional heat illness (such as heat stroke and muscle cramps) each year, with the greatest risk among high school football players.145,146 This appears to be a worsening trend. Between 1997 and 2006, emergency department visits for all heat-related illness increased 133% and youth made up almost 50% of those cases.147 From 2000 through 2013, the number of deaths due to heat stroke doubled among U.S. high school and college football players.148 Other data show effects of extreme heat on children of all ages, including increases in heat illness, fluid and electrolyte imbalances, and asthma. Children in homes or schools without air conditioning are also more vulnerable during heat events.

Other weather extremes. Climate change is likely to affect the mental health and well-being of children, primarily by increasing exposure to traumatic weather events that result in injury, death, or displacement. In 2003, more than 10% of U.S. children from infancy to 18 years of age reported experiencing a disaster (fire, tornado, flood, hurricane, earthquake, etc.) during their lifetimes.149 Exposures to traumatic events can impact children’s capacity to regulate emotions, undermine

Degraded air quality. Several factors make children more sensitive to the effects of respiratory hazards, including lung development that continues through adolescence, the size of the child’s airways, their level of physical activity, and body weight. Climate change has the potential to affect future ground-level ozone concentrations, particulate matter concentrations, and levels of some aeroallergens. Ground-level ozone and particulate matter are associated with increases in asthma episodes and other adverse respiratory effects in children.151,152,153 Nearly seven million, or about 9%, of children in the United States, suffer from asthma.154 Asthma accounts for 10 million missed school days each year.155 Particulate matter such as dust and

Changes in climate also contribute to longer, more severe pollen seasons that may be associated with increases in childhood asthma episodes and other allergic illnesses. Children may also be exposed to indoor air pollutants, including both particulate matter originating outdoors and indoor sources such as tobacco smoke and mold. In addition, high outdoor temperatures may increase the amount of time children spend indoors. Homes, childcare centers, and schools—places where children spend large amounts of their time—are all settings where indoor air quality issues may affect children’s health. In communities where these buildings are insufficiently supplied with screens, air conditioning, humidity controls, or pest control, children’s health may be at risk.157 (See Ch. 3: Air Quality Impacts).

Waterborne illnesses. Climate change induced increases in heavy rainfall, flooding, and coastal storm events are expected to increase children’s risk of gastrointestinal illness from ingestion of or contact with contaminated water.61,142,143,158 An increased association between heavy rainfall and increased acute gastrointestinal illness has already been observed in children in the United States.159 Children may be especially vulnerable to recreational exposures to waterborne pathogens, in part because they swallow roughly twice as much water as adults while swimming.160 In addition, children comprised 40% of swimming-related eye and ear infections from the waterborne bacteria Vibrio alginolyticus during the period 1997–2006161 and 66% (ages 1–19) of those seeking treatment for illness associated with harmful

Vector-borne and other infectious diseases. The changes in the distribution of infectious diseases that are expected to result from climate change may introduce new exposures to children (see Ch. 5: Vector-Borne Disease). Due to physiological vulnerability or changes in their body’s immune system, fetuses, pregnant women, and children are at increased risk of acquiring or having complications from certain infectious diseases such as listeriosis,163

Food safety and security. Climate change, including rising levels of atmospheric CO2, significantly reduces food quality and threatens availability and access for children. Because of the importance of nutrition during certain stages of physical and mental growth and development, the direct effect of the continued rise of CO2 on reducing food quality will be an increasingly significant issue for children globally.169,170,171 For the United States, disruptions in food production or distribution due to extreme events such as drought can increase costs and limit availability or access,172,173 particularly for food-insecure households, which include nearly 16% of households with children in the United States.174 Children are also more susceptible to severe infection or complications from Escherichia coli infections, such as hemolytic uremic syndrome.175 (See Ch. 7: Food Safety).

Vulnerability Related to Life Stage

Prenatal and pregnancy outcomes for mothers and babies. Climate-related exposures may lead to adverse pregnancy and newborn health outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, low birth weight (less than 5.5 pounds), preterm birth (birth before 37 weeks of pregnancy), increased neonatal death, dehydration and associated

In addition, exposure of pregnant women to inhaled particulate matter is associated with negative birth outcomes.184,185,186,187,188,189 Incidences of diarrheal diseases and dehydration may increase in extent and severity, which can be associated with adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes and the health of newborns.176 Floods are associated with an increased risk of maternal exposure to environmental toxins and mold, reduced access to safe food and water, psychological stress, and disrupted health care. Other flood-related health outcomes for mothers and babies include maternal risk of anemia (a condition associated with low red blood cell counts sometimes caused by low iron intake), eclampsia (a condition that can cause seizures in pregnant women), and spontaneous abortion.190,191,192,193

Infants and toddlers. Infants and toddlers are particularly sensitive to air pollutants, extreme heat, and

Older Adults

Older adults (generally defined as persons aged 65 and older) are vulnerable to the health impacts associated with climate change and weather extremes.11,197,198,199 The number of older adults in the United States is projected to grow substantially in the coming decades. The nation’s older adult population (ages 65 and older) will nearly double in number from 2015 through 2050, from approximately 48 million to 88 million.200 Of those 88 million older adults, a little under 19 million will be 85 years of age and older.201 This projected population growth is largely due to the aging of the Baby Boomer generation (an estimated 76 million people born in the United States between 1946 and 1964), along with increases in lifespan and survivorship.18 Older adults in the United States are not uniform with regard to their climate-related vulnerabilities, but are a diverse group with distinct subpopulations that can be identified not only by age but also by race, educational attainment, socioeconomic status, social support networks, overall physical and mental health, and

Vulnerability to Climate-Related Health Stressors

The potential climate change related health impacts for older adults include rising temperatures and heat waves; increased risk of more intense hurricanes (Categories IV and V), floods, droughts, and wildfires; degraded air quality; exposure to infectious diseases; and other climate-related hazards.120

Extreme heat events. Older adults exposed to extreme heat can experience multiple adverse effects.203 In the coming decades, extreme heat events are projected to become more frequent, more intense, and of longer duration, especially in higher latitudes and large metropolitan areas.24,204 Between 1979 and 2004, 5,279 deaths were reported in the United States related to heat exposure, with those deaths reported most commonly among adults aged 65 and older.205 Disease incidence among older adults is expected to increase even in regions with relatively modest temperature changes (as demonstrated by case studies of a 2006 California

Other weather extremes. Hurricanes and other severe weather events lead to physical, mental, or emotional trauma before, during, and after the event.208 The need to evacuate an area can pose increased health and safety risks for older adults, especially those who are poor or reside in nursing or assisted-living facilities.209,210 Moving patients to a sheltering facility is complicated, costly, and time-consuming and requires concurrent transfer of medical records, medications, and medical equipment (see also Ch. 4: Extreme Events).210,211

Degraded air quality. Climate change can affect air quality by increasing ground-level ozone, fine particulate matter, aeroallergens, wildfire smoke, and dust (see Ch. 3: Air Quality Impacts).212,213 Exposure to ground-level ozone varies with age and can affect lung function and increase emergency department visits and hospital admissions, even for healthy adults. Air pollution can also exacerbate asthma and COPD and can increase the risk of heart attack in older adults, especially those who are also diabetic or obese.214

Vector-borne and waterborne diseases. The changes in the distribution of disease vectors like ticks and mosquitoes that are expected to result from climate change may increase exposures to pathogens in older adult populations (see Ch. 5: Vector-Borne Diseases). Some vector-borne diseases, notably mosquito-borne West Nile and St. Louis encephalitis viruses,215,216 pose a greater health risk among sensitive older adults with already compromised immune systems. Climate change is also expected to increase exposure risk to waterborne pathogens in sources of drinking water and recreational water. Older adults have a higher risk of contracting gastrointestinal illnesses from contaminated drinking and recreational water and suffering severe health outcomes and death (see Ch. 6: Water-Related Illness).217,218,219,220

Interactions with Non-Climate Stressors

Vulnerable locations and condition of the built environment. Older adults are particularly vulnerable to climate change related health effects depending on their geographic location and characteristics of their homes, such as the quality of construction and amenities. More than half of the elderly U.S. adult population is concentrated in 170 counties (5% of all U.S. counties), and approximately 20% of older Americans live in a county in which a hurricane or tropical storm made landfall over the last decade.221 For example, Florida is a traditional retirement destination with an older adult population accounting for 16.8% of the total in 2010, nearly four percentage points higher than the national average.222 The increasing severity of tropical storms may pose particular risks for older adults in coastal zones.223 Other geographic risk factors common to older adults are the

In neighborhoods where safety and crime are a concern, older residents may fear venturing out of their homes, thus increasing their social isolation and risk of health impacts during events such as heat waves.224 Degraded infrastructure, including the condition of housing and public transportation, is associated with higher numbers of heat-related deaths in older adults. In multi-story residential buildings in which residents rely on elevators, electricity loss makes it difficult, if not impossible, for elderly residents and those with disabilities to leave the building to obtain food, medicine, and other needed services.226 Also, older adults who own air-conditioning units may not utilize them during heat waves due to high operating costs.11,227,228,229

Vulnerability related to physiological factors. Older adults are more sensitive to weather-related events due to age-related physiological factors. Elevated risks for cardiovascular deaths related to exposure to extreme heat have been observed in older adults.32,230 Generally poorer physical health conditions, such as long-term chronic illnesses, are exacerbated by climate change.227,228,231,232 In addition, aging can impair the mechanisms that regulate body temperature, particularly for those taking medications that interfere with regulation of body temperature, including psychotropic medications used to treat a variety of

Vulnerability related to disabilities. Some functional limitations and mobility impairments increase older adults’ sensitivity to climate change, particularly extreme events. In 2010, 49.8% of older adults (over 65) were reported to have a disability, compared to 16.6% of people aged 21–64.234 Dementia occurs at a rate of 5% of the U.S. population aged 71 to 79 years, with an increase to more than 37% at age 90 and older.235 Older adults with mobility or cognitive impairments are likely to experience greater vulnerability to health risks due to difficulty responding to, evacuating, and recovering from extreme events.11,231

Occupational Groups

Climate change may increase the prevalence and severity of known occupational hazards and exposures, as well as the emergence of new ones. Outdoor workers are often among the first to be exposed to the effects of climate change. Climate change is expected to affect the health of outdoor workers through increases in ambient temperature, degraded air quality, extreme weather, vector-borne diseases, industrial exposures, and changes in the built environment.10 Workers affected by climate change include farmers, ranchers, and other agricultural workers; commercial fishermen; construction workers; paramedics, firefighters and other first responders; and transportation workers. Also, laborers exposed to hot indoor work environments (such as steel mills, dry cleaners, manufacturing facilities, warehouses, and other areas that lack air conditioning) are at risk for extreme heat exposure.236,237,238

For some groups, such as migrant workers and day laborers, the health effects of climate change can be cumulative, with occupational exposures exacerbated by exposures associated with poorly insulated housing and lack of air conditioning. Workers may also be exposed to adverse occupational and climate-related conditions that the general public may altogether avoid, such as direct exposure to wildfires.

Extreme heat events. Higher temperatures or longer, more frequent periods of heat may result in more cases of heat-related illnesses (for example, heat stroke and heat exhaustion) and fatigue among workers,237,238,239,240,241 especially among more physically demanding occupations. Heat stress and fatigue can also result in reduced vigilance, safety lapses, reduced work capacity, and increased risk of injury. Elevated temperatures can increase levels of air pollution, including ground-level ozone, resulting in increased worker exposure and subsequent risk of respiratory illness (see also Ch. 2: Temperature-Related Death and Illness).10,236,237,242

Other weather extremes. Some extreme weather events and natural disasters, such as floods, storms, droughts, and wildfires, are becoming more frequent and intense (see also Ch. 4: Extreme Events).120 An increased need for complex emergency responses will expose rescue and recovery workers to physical and psychological hazards.205,243 The safety of workers and their ability to recognize and avoid workplace hazards may be impaired by damage to infrastructure and disrupted communication.

From 2000 to 2013, almost 300 U.S. wildfire firefighters were killed while on duty.244 With the frequency and severity of wildfires projected to increase, more firefighters will be exposed. Common workplace hazards faced on the fire line include being overrun by fire (as happened during the Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona in 2013 that killed 19 firefighters);245 heat-related illnesses and injuries; smoke inhalation; vehicle-related injuries (including aircraft); slips, trips, and falls; and exposure to particulate matter and other air pollutants in wildfire smoke. In addition, wildland fire fighters are at risk of rhabdomyolysis (a breakdown of muscle tissue) that is associated with prolonged and intense physical exertion.246

Other workplace exposures to outdoor health hazards. Other climate-related health threats for outdoor workers include increased waterborne and foodborne pathogens, increased duration of aeroallergen exposure with longer pollen seasons,247,248 and expanded habitat ranges of disease-carrying vectors that may influence the risk of human exposure to diseases such as West Nile virus or Lyme disease (see also Ch. 5: Vector-Borne Diseases).249

Persons with Disabilities

Disability refers to any condition or impairment of the body or mind that limits a person’s ability to do certain activities or restricts a person’s participation in normal life activities, such as school, work, or recreation.250 The term “disability” covers a wide variety and range of functional limitations related to expressive and receptive communication (hearing and speech), vision, cognition, and mobility. These factors, if not anticipated and accommodated before, during, and after extreme events, can result in illness and death.251 The extent of disability, or its severity, is reflected in the affected person’s need for environmental accessibility and accommodations for their impairment(s).252

Persons with disabilities often rely on medical equipment (such as portable oxygen) that requires an uninterrupted source of electricity.

© iStockPhotos.com/ ozgurkeser

Disability can occur at any age and is not uniformly distributed across populations. Disability varies by gender, race, ethnicity, and geographic location.253 Approximately 18.7% of the U.S. population has a disability.234 In 2010, the percent of American adults with a disability was approximately 16.6% for those aged 18–64 and 49.8% for persons 65 and older.234 In 2014, working-age adults with disabilities were substantially less likely to participate in the labor force (30.2%) than people without disabilities (76.2%), and experience more than twice the rate of unemployment (13.9% and 6.0%, respectively).254

People with disabilities experience disproportionately higher rates of social risk factors, such as poverty and lower educational attainment, that contribute to poorer health outcomes during extreme events or climate-related emergencies. These factors compound the risks posed by functional impairments and disrupt planning and emergency response. Of the climate-related health risks experienced by people with disabilities, perhaps the most fundamental is their “invisibility” to decision-makers and planners.255 There has been relatively limited empirical research documenting how people with disabilities fare during or after an extreme event.256

An increase in extreme weather can be expected to disproportionately affect populations with disabilities unless emergency planners make provisions to address their functional needs in preparing emergency response plans. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina had a significant and disproportionate impact on people with disabilities. Of the 986 deaths in Louisiana directly attributable to the storm, 103 occurred among individuals in nursing homes, presumably with a disability.257 Strong social capital and societal connectedness to other people, especially through faith-based organizations, family networks, and work connections, were considered to be key enabling factors that helped people with disabilities to cope before, during, and after the storm.258 In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, the City of New York lost a lawsuit filed by the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled (Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled et al. v. Bloomberg et al., Case 1.11-cv-06690-JMF 2013), with the finding that the city had not adequately prepared to accommodate the social and medical support needs of New York residents with disabilities.

Risk communication is not always designed or delivered in an accessible format or media for individuals who are deaf or have hearing loss, who are blind or have low vision, or those with diminished cognitive skills.259,260 Emergency communication and other important notifications (such as a warning to boil contaminated water) simply may not reach persons with disabilities. In addition, persons with disabilities often rely on medical equipment (such as portable oxygen) that requires an uninterrupted source of electricity. Portable oxygen supplies must be evacuated with the patient.261

Persons with Chronic Medical Conditions

Preexisting medical conditions present risk factors for increased illness and death associated with climate-related stressors, especially exposure to extreme heat. In some cases, risks are mediated by the physiology of specific medical conditions that may impair responses to heat exposure. In other cases, the risks are related to unintended side effects of medical treatment that may impair body temperature, fluid, or electrolyte balance and thereby increase risks. Trends in the prevalence of chronic medical conditions are summarized in Table 1.1 in Chapter 1: Introduction. In general, the prevalence of common chronic medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, diabetes, asthma, and obesity, is anticipated to increase over the coming decades (see Table 1.1 in Ch. 1: Introduction), resulting in larger populations at risk of medical complications from climate change related exposures.

Excess heat exposure has been shown to increase the risk of disease exacerbation or death for people with various medical conditions. Hospital admissions and emergency room visits increase during heat waves for people with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and psychiatric illnesses.40,58,195,262,263,264,265,266 Medical conditions like Alzheimer’s disease or mental illnesses can impair judgment and behavioral responses in crisis situations, which can place people with those conditions at greater risk.228

Medications used to treat chronic medical conditions are associated with increased risk of hospitalization, emergency room admission, and in some cases, death from extreme heat. These medicines include drugs used to treat neurologic or psychiatric conditions, such as anti-psychotic drugs, anti-cholinergic agents, anxiolytics (anti-anxiety medicines), and some antidepressants (such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs; see also Ch. 8: Mental Health).233,267,268 In addition, drugs used to treat cardiovascular diseases, such as diuretics and beta-blockers, may impair resilience to heat stress.267,269

People with chronic medical conditions also can be more vulnerable to interruption in treatment. For example, interrupting treatment for patients with addiction to drugs or alcohol may lead to withdrawal syndromes.270,271,272 Treatment for chronic medical conditions represents a significant proportion of post-disaster medical demands.273 Communities that are both medically underserved and have a high prevalence of chronic medical conditions can be especially at risk.274 While most studies have assessed adults, and especially the elderly, with chronic medical conditions, children with medical conditions such as allergic and respiratory diseases are also at greater risk of symptom exacerbation and hospital admission during heat waves.144

Approaches to Assessing Vulnerability

Figure 9.4: Mapping Social Vulnerability

VIEWThere are multiple approaches for developing vulnerability indices to identify populations of concern across large areas, such as state or multistate regions, or small areas, such as households within a county or several counties within a state.292 The Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) developed by the CDC aggregates U.S. census data to estimate the social vulnerability of census tracts (which are generally subsets of counties; Figure 9.4). The SVI provides a measure of overall social vulnerability in addition to measures of elements that comprise social vulnerability (including socioeconomic status, household composition, race or ethnicity, native language, and

Application of Vulnerability Indices

GIS—data management systems used to capture, store, manage, retrieve, analyze, and display geographic information—can be used to quantify and visualize factors that contribute to climate-related health risks. By linking together census data, data on the determinants of health (social, environmental, preexisting health conditions), measures of adaptive capacity (such as health care access), and climate data, GIS mapping helps identify and position resources for at-

Vulnerability mapping can also enhance emergency and disaster risk management.297,298 Vulnerability mapping conducted at finer spatial resolution (for example, census tracts or census blocks) allows public health departments to target vulnerable communities for emergency

Emergency response agencies can apply lessons learned by mapping prior events. For example, vulnerability mapping has been used to assess how social disparities affected the geography of recovery in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina.8 Maps displaying the intersection of social vulnerability (low, medium, high scores) and flood inundation (none, low, medium, high levels) showed that while the physical manifestation of the disaster had few race or class distinctions, the social vulnerability of communities influenced both pre-impact responses, such as evacuation, and post-event recovery.8 As climate change increases the probability of more frequent or more severe extreme

A number of research needs related to

More comprehensive and robust projections of factors that contribute to population vulnerability would also enhance the value of predictive models. At present, there are only limited projections of health status of the U.S. population, and the U.S. Census no longer provides population projections at the state level. Projecting population vulnerability into the future, as well as the development of consensus storylines that characterize alternative socioeconomic scenarios, will facilitate more robust and useful assessments of future health impacts of climate change.

Future assessments can benefit from research activities that:

- improve understanding of the relative contributions and causal mechanisms of vulnerability factors (for example, genetic, physiological, social, behavioral) to risks of specific health impacts of climate change;

- investigate how available sources of data on population characteristics can be used to create valid indicators and help map vulnerability to the health impacts of climate change;

- understand how vulnerability to both medical and

psychological health impacts of climate change affect cumulative stress and health status; and - evaluate the efficacy of measures designed to enhance

resilience and reduce the health impacts from climate change at the individual, institutional, and community levels.

References

- , 2012: Environmental justice and infectious disease: Gaps, issues, and research needs. Environmental Justice, 5, 8-20. doi:10.1089/env.2010.0043 | Detail

- 2004: Impacts of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. 140 pp., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. URL | Detail

- 2007: Leishmaniasis in relation to service in Iraq/Afghanistan, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2006. MSMR: Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, 14(1), 2-5. URL | Detail

- 2015: Update: Heat injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces. MSMR: Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, 22(3), 17-20. URL | Detail

- 2015: Chikungunya in the Americas Surveillance Summary. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. URL | Detail

- , 2012: Floods and human health: A systematic review. Environment International, 47, 37-47. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2012.06.003 | Detail

- , 2008: Perception of change in freshwater in remote resource-dependent Arctic communities. Global Environmental Change, 18, 153-164. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.05.007 | Detail

- 2014: Brief report: the geographic distribution of incident coccidioidomycosis among active component service members, 2000-2013. MSMR: Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, 21, 12-14. PMID: 24978473 | Detail

- 2015: Update: Malaria, U.S. Armed Forces, 2014. MSMR: Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, 22, 2-6. PMID: 25643089 | Detail

- , 2009: Providing continuity of care for chronic diseases in the aftermath of Katrina: From field experience to policy recommendations. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 3, 174-182. doi:10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181b66ae4 | Detail

- , 2011: Heat wave impact on morbidity and mortality in the elderly population: A review of recent studies. Maturitas, 69, 99-105. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.03.008 | Detail

- cited 2015: Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) Mapping Dashboard. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. URL | Detail

- , 2000: First records of sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka) and pink salmon (O. gorbuscha) from Banks Island and other records of Pacific salmon in Northwest Territories, Canada. Arctic, 53, 161-164. doi:10.14430/arctic846 | Detail

- , 2010: Traffic-related air pollution and QT interval: Modification by diabetes, obesity, and oxidative stress gene polymorphisms in the normative aging study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118, 840-846. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901396 | Detail

- , 2009: Identifying vulnerable subpopulations for climate change health effects in the United States. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 51, 33-37. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318193e12e | Detail

- , 2007: Air pollution and allergens. Journal of Investigational Allergology and Clinical Immunology, 17 Suppl 2, 3-8. URL | Detail

- , 2009: High ambient temperature and mortality: A review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environmental Health, 8, 40. doi:10.1186/1476-069x-8-40 | Detail

- , 2008: A multicounty analysis identifying the populations vulnerable to mortality associated with high ambient temperature in California. American Journal of Epidemiology, 168, 632-637. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn170 | Detail

- , 2010: High ambient temperature and the risk of preterm delivery. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172, 1108-1117. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq170 | Detail

- , 2010: Disasters, victimization, and children’s mental health. Child Development, 81, 1040-1052. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01453.x | Detail

- , 2011: Climate change and childrenʼs health. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 23, 221-226. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283444c89 | Detail

- , 2014: Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. 161 pp., National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. URL | Detail

- , 1994: At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability, and Disasters. Routledge, 284 pp. | Detail

- cited 2015: Economic News Release: Table A. Employment Status of the Civilian Noninstitutional Population by Disability Status and Age, 2012 and 2013 Annual Averages. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. URL | Detail

- , 2005: Mercury, food webs, and marine mammals: Implications of diet and climate change for human health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113, 521-526. doi:10.1289/ehp.7603 | Detail

- , 2011: Regional differences in the association between land cover and West Nile virus disease incidence in humans in the United States. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 84, 234-238. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0134 | Detail

- , 2012: Americans With Disabilities: 2010. 23 pp., U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- , 2005: Socioeconomic status in health research: One size does not fit all. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 294, 2829-2888. doi:10.1001/jama.294.22.2879 | Detail

- , 2011: The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 381-398. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218 | Detail

- , 2006: Neighborhood social processes, physical conditions, and disaster-related mortality: The case of the 1995 Chicago heat wave. American Sociological Review, 71, 661-678. doi:10.1177/000312240607100407 | Detail

- , 2015: Climate Change, Global Food Security and the U.S. Food System. 146 pp., U.S. Global Change Research Program. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Hurricane Katrina deaths, Louisiana, 2005. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 2, 215-223. doi:10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818aaf55 | Detail

- , 2009: Introduction. Race, Place, and Environmental Justice After Hurricane Katrina, Struggles to Reclaim Rebuild, and Revitalize New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, , Westview Press, 1-15. | Detail

- , 2014: Extreme precipitation and beach closures in the Great Lakes region: Evaluating risk among the elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 2014-2032. doi:10.3390/ijerph110202014 | Detail

- , 2007: Health concerns of women and infants in times of natural disasters: Lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11, 307-311. doi:10.1007/s10995-007-0177-4 | Detail

- , 2009: Lessons learned from the deadly sisters: Drug and alcohol treatment disruption, and consequences from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Substance Use & Misuse, 44, 1681-1694. doi:10.3109/10826080902962011 | Detail

- , 2014: Ch. 17: Southeast and the Caribbean. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, , U.S. Global Change Research Program, 396-417. doi:10.7930/J0NP22CB | Detail

- 2008: Analyses of the Effects of Global Change on Human Health and Welfare and Human Systems. A report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. , U.S. Climate Change Science Program, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. URL | Detail

- 2011: Health Disparities and Inequalities Report-United States, 2011. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(Suppl), 1-116. URL | Detail

- cited 2012: Table 2-1: Lifetime Asthma Prevalence Percents by Age, United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- 2013: Health Disparities and Inequalities Report--United States 2013. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(Supp.3), 1-187. URL | Detail

- cited 2014: Health, United States, 2013--At a Glance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- cited 2014: Diabetes Public Health Resource: Rate per 100 of Civilian, Noninstitutionalized Population with Diagnosed Diabetes, by Age, United States, 1980-2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- cited 2015: Confirmed Lyme Disease Cases by Age and Sex--United States, 2001-2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- cited 2015: Disability and Health: Disability Overview. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- cited 2015: Reproductive Health: Preterm Birth. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- , 2010: Cognitive and psychosocial consequences of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita among middle-aged, older, and oldest-old adults in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study (LHAS). Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 2463-2487. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00666.x | Detail

- , 2013: Adapting to the Effects of Climate Change on Wild Rice. 12 pp., Great Lakes Lifeways Institute. | Detail

- , 2011: Maternal and fetal outcome of dengue fever during pregnancy. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases, 48, 210-213. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Prenatal exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and risk of intrauterine growth restriction. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116, 658-665. doi:10.1289/ehp.10958 | Detail

- , 2012: Household Food Security in the United States in 2011. 29 pp., U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. URL | Detail

- , 2013: Hispanic health disparities after a flood disaster: Results of a population-based survey of individuals experiencing home site damage in El Paso (Texas, USA). Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15, 415-426. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9626-2 | Detail

- , 2007: General and specific mortality among the elderly during the 2003 heat wave in Genoa (Italy). Environmental Research, 103, 267-274. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2006.06.003 | Detail

- , 2013: Climate change impacts on the water resources of American Indians and Alaska Natives in the U.S. Climatic Change, 120, 569-584. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0852-y | Detail

- , 2014: Incidence and trends of infections with pathogens transmitted commonly through food--Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. sites, 2006-2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63, 328-332. URL | Detail

- , 2010: Deciphering the effect of climate change on landslide activity: A review. Geomorphology, 124, 260-267. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2010.04.009 | Detail

- , 2007: Coccidioidomycosis in the U.S. Military: A Review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1111, 112-121. doi:10.1196/annals.1406.001 | Detail

- 2008: Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 247 pp., World Health Organization, Geneva. URL | Detail

- , 2015: Examining relationships between climate change and mental health in the Circumpolar North. Regional Environmental Change, 15, 169-182. doi:10.1007/s10113-014-0630-z | Detail

- , 2013: The land enriches the soul: On climatic and environmental change, affect, and emotional health and well-being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emotion, Space and Society, 6, 14-24. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2011.08.005 | Detail

- , 2010: The impact of disasters on populations with health and health care disparities. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 4, 30-38. doi:10.1017/S1935789300002391 | Detail

- , 2008: Nonfoodborne Vibrio infections: An important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, 1997–2006. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 46, 970-976. doi:10.1086/529148 | Detail

- , 2012: National and Regional Associations Between Human West Nile Virus Incidence and Demographic, Landscape, and Land Use Conditions in the Coterminous United States. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 12, 657-665. doi:10.1089/vbz.2011.0786 | Detail

- , 1999: Fetal growth and maternal exposure to particulate matter during pregnancy. Environmental Health Perspectives, 107, 475-480. URL | Detail

- 2001: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, Rockville, MD. URL | Detail

- 2009: A Profile of Older Americans: 2009. 17 pp., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- 2014: National Healthcare Disparities Report 2013. Array, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. URL | Detail

- , 2013: Experimental and natural warming elevates mercury concentrations in estuarine fish. PLoS ONE, 8, e58401. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058401 | Detail

- 2010: Quadrennial Defense Review Report. 105 pp., U.S. Department of Defense. URL | Detail

- cited 2012: Department of Defense FY 2012 Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap. Appendix to DOD's Strategic Sustainability Performance Plan 2012. U.S. Department of Defense. URL | Detail

- 2014: Quadrennial Defense Review. 64 pp., U.S. Department of Defense. URL | Detail

- , 2000: Asthma and PM10. Respiratory Research, 1, 12-15. doi:10.1186/rr5 | Detail

- , 2014: Indigenous community health and climate change: Integrating biophysical and social science indicators. Coastal Management, 42, 355-373. doi:10.1080/08920753.2014.923140 | Detail

- , 2011: Poisoning the body to nourish the soul: Prioritising health risks and impacts in a Native American community. Health, Risk & Society, 13, 103-127. doi:10.1080/13698575.2011.556186 | Detail

- , 2008: Population composition, migration and inequality: The influence of demographic changes on disaster risk and vulnerability. Social Forces, 87, 1089-1114. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0141 | Detail

- , 2013: Exploring effects of climate change on Northern Plains American Indian health. Climatic Change, 120, 643-655. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0799-z | Detail

- , 2013: Recent seasonal variations in arid landscape cover and aeolian sand mobility, Navajo Nation, southwestern United States. Climates, Landscapes, and Civilizations, , American Geophysical Union, 51-60. doi:10.1029/2012GM001214 | Detail

- , 2010: Association between rainfall and pediatric emergency department visits for acute gastrointestinal illness. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118, 1439-1443. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901671 | Detail

- , 2009: Minnesota's moose: Ghosts of the northern forest? Bioscience, 59, 824-828. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.10.3 | Detail

- , 2013: Protecting Health from Climate Change: Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment. 62 pp., World Health Organization, Geneva. URL | Detail

- , 2006: The asthma epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 355, 2226-2235. doi:10.1056/NEJMra054308 | Detail

- , 2013: Health disparities: Promoting indigenous peoples' health through traditional food systems and self-determination. Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems & Well-Being: Interventions & Policies for Healthy Communities, , Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 9-22. URL | Detail

- , 2007: Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health, 97, S109-S115. doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.084335 | Detail

- , 2014: Parental limited English proficiency and health outcomes for children with special health care needs: A systematic review. Academic Pediatrics, 14, 128-136. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.10.003 | Detail

- 2010: Our Nation’s Air: Status and Trends through 2008. 54 pp., U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Research Triangle Park, NC. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Meeting the Access Goal: Strategies for Increasing Access to Safe Drinking Water and Wastewater Treatment to American Indian and Alaska Native Homes. Infrastructure Task Force Access Subgroup, 2008. 34 pp., U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. URL | Detail

- , 2002: La Crosse encephalitis in eastern Tennessee: Clinical, environmental, and entomological characteristics from a blinded cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 155, 1060-1065. doi:10.1093/aje/155.11.1060 | Detail

- , 2014: Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives. American Journal of Public Health, 104, S303-S311. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301798 | Detail

- , 2002: Increasing habitat suitability in the United States for the tick that transmits Lyme disease: A remote sensing approach. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110, 635-640. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 316-338. doi:10.1177/0886260507312290 | Detail

- , 2014: Child traumatic stress: Prevalence, trends, risk, and impact. Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice, , Guilford Press, 121-145. | Detail

- , 2010: Older people and climate change: Vulnerability and health effects. Generations, 33, 19-25. URL | Detail

- , 2010: Disaster disparities and differential recovery in New Orleans. Population and Environment, 31, 179-202. doi:10.1007/s11111-009-0099-8 | Detail

- , 2003: Relation between income, air pollution and mortality: A cohort study. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 169, 397-402. URL | Detail

- , 2014: Adapting to the effects of climate change on Inuit health. American Journal of Public Health, 104 Suppl 3, e9-e17. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301724 | Detail

- , 2004: A framework for assessing the vulnerability of communities in the Canadian arctic to risks associated with climate change. Arctic, 57, 389-400. doi:10.14430/arctic516 | Detail

- , 2004: Poverty and disasters in the United States: A review of recent sociological findings. Natural Hazards, 32, 89-110. doi:10.1023/B:NHAZ.0000026792.76181.d9 | Detail

- , 2010: The psychosocial impact of Hurricane Katrina on persons with disabilities and independent living center staff living on the American Gulf Coast. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55, 231-240. doi:10.1037/a0020321 | Detail

- , cited 2011: The New Metro Minority Map: Regional Shifts in Hispanics, Asians, and Blacks from Census 2010. Brookings Institution. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Global health equity and climate stabilisation: A common agenda. The Lancet, 372, 1677-1683. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61692-x | Detail

- , 2002: Urban sprawl and public health. Public Health Reports, 117, 201-217. PMID: 12432132 | Detail

- , 2008: Climate change: The public health response. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 435-445. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.119362 | Detail

- , 2009: Immigration status and use of health services among Latina women in the San Francisco Bay Area. Journal of Women's Health, 18, 1275-1280. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1241 | Detail

- , 2013: Climate change and older Americans: State of the science. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 15-22. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205223 | Detail

- , 2004: Cultural keystone species: Implications for ecological conservation and restoration. Ecology and Society, 9, 1. URL | Detail

- , 2004: The effect of air pollution on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age. New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 1057-1067. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040610 | Detail

- , 2012: Dengue and US military operations from the Spanish-American War through today. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 18, 623-630. doi:10.3201/eid1804.110134 | Detail

- , 2010: Heat illness among high school athletes - United States, 2005-2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59, 1009-1013. PMID: 20724966 | Detail

- , 2011: Epidemiology of sports injury in pediatric athletes. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 19, 2-6. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e31820b95fc | Detail

- , 2010: The effect of temperature on hospital admissions in nine California counties. International Journal of Public Health, 55, 113-121. doi:10.1007/s00038-009-0076-0 | Detail

- , 2014: The epidemiology of occupational heat exposure in the United States: A review of the literature and assessment of research needs in a changing climate. International Journal of Biometeorology, 58, 1779-1788. doi:10.1007/s00484-013-0752-x | Detail

- , 2001: Climate variability and change in the United States: Potential impacts on vector- and rodent-borne diseases. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109, 223-233. doi:10.2307/3435012 | Detail

- , 1999: Preparing for a Changing Climate: The Potential Consequences of Climate Variability and Change in Alaska. A Report of the Alaska Regional Assessment Group for the U.S. Global Change Research Program. Center for Global Change and Arctic System Research, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 42 pp. URL | Detail

- , 2001: The burden of air pollution: Impacts among racial minorities. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109, 501-506. URL | Detail

- , 2009: The effect of Hurricane Katrina: Births in the U.S. Gulf Coast region, before and after the storm. National Vital Statistics Reports, 58, 1-28, 32. PMID: 19754006 | Detail

- , 2008: The effect of heat waves on hospital admissions for renal disease in a temperate city of Australia. International Journal of Epidemiology, 37, 1359-1365. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn165 | Detail

- , 2011: Older persons and heat-susceptibility: The role of health promotion in a changing climate. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 22, 17-20. doi:10.1071/HE11417 | Detail

- , 2011: Perceptions of heat-susceptibility in older persons: Barriers to adaptation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8, 4714-4728. doi:10.3390/ijerph8124714 | Detail

- , 2008: Growing Old in a Changing Climate: Meeting the Challenges of an Ageing Population and Climate Change. 28 pp., Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. URL | Detail

- , 2015: Dynamic decision processes in complex, high-risk operations: The Yarnell Hill Fire, June 30, 2013. Safety Science, 71(Part A), 39-47. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2014.04.019 | Detail

- , 2006: Neighborhood microclimates and vulnerability to heat stress. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 2847-2863. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.030 | Detail

- , 2013: Neighborhood effects on heat deaths: Social and environmental predictors of vulnerability in Maricopa County, Arizona. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 197-204. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104625 | Detail

- , 2009: Hurricane Katrina and perinatal health. Birth, 36, 325-331. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00360.x | Detail

- , 2009: Prognostic factors in non-exertional heatstroke. Intensive Care Medicine, 36, 272-280. doi:10.1007/s00134-009-1694-y | Detail

- , 2008: The relationship between in-home water service and the risk of respiratory tract, skin, and gastrointestinal tract infections among rural Alaska natives. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 2072-2078. doi:10.2105/ajph.2007.115618 | Detail

- , 2014: Summertime acute heat illness in U.S. emergency departments from 2006 through 2010: Analysis of a nationally representative sample. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122, 1209-1215. doi:10.1289/ehp.1306796 | Detail

- , 2014: Algal bloom-associated disease outbreaks among users of freshwater lakes--United States, 2009-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63, 11-15. PMID: 24402467 | Detail

- , 2005: Evidence and implications of recent climate change in Northern Alaska and other Arctic regions. Climatic Change, 72, 251-298. doi:10.1007/s10584-005-5352-2 | Detail

- , 2010: A Native American perspective on spiritual assessment: The strengths and limitations of a complementary set of assessment tools. Health & Social Work, 35, 121-131. doi:10.1093/hsw/35.2.121 | Detail

- , 2009: Moving from colonization toward balance and harmony: A Native American perspective on wellness. Social Work, 54, 211-219. doi:10.1093/sw/54.3.211 | Detail

- , 2012: Indigenous peoples of North America: Environmental exposures and reproductive justice. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120, 1645-1649. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205422 | Detail

- 2007: Measuring Overcrowding in Housing. 38 pp., U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. URL | Detail

- , 2011: Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010. 23 pp., U.S. Census Bureau. URL | Detail

- , 2014: The geographic distribution of incident Lyme disease among active component service members stationed in the continental United States, 2004-2013. MSMR: Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, 21, 13-15. PMID: 24885878 | Detail

- , 2010: Vulnerability of children: More than a question of age. Radiation Protection Dosimetry, 142, 54-57. doi:10.1093/rpd/ncq200 | Detail

- , 2004: Burden of self‐reported acute diarrheal illness in FoodNet surveillance areas, 1998–1999. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 38, S219-S226. doi:10.1086/381590 | Detail

- 2010: Providing Healthy and Safe Foods As We Age: Workshop Summary. Institute of Medicine. The National Academies Press, 192 pp. URL | Detail

- 2014: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1132 pp., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY. URL | Detail

- , 2012: Seasonal patterns of gastrointestinal illness and streamflow along the Ohio River. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9, 1771-1790. doi:10.3390/ijerph9051771 | Detail

- , 2008: Listeriosis in pregnancy: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1, 179-185. URL | Detail

- , 2012: Disaster resilience and people with functional needs. New England Journal of Medicine, 367, 2272-2273. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1213492 | Detail

- , 2009: Air quality and early-life mortality: Evidence from Indonesia’s wildfires. The Journal of Human Resources, 44, 916-954. doi:10.3368/jhr.44.4.916 | Detail

- , 2013: The racial/ethnic distribution of heat risk–related land cover in relation to residential segregation. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 811-817. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205919 | Detail

- , 2007: Chronic disease and disasters: Medication demands of Hurricane Katrina evacuees. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33, 207-210. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.030 | Detail

- , 2014: Conceptualizing health consequences of Hurricane Katrina from the perspective of socioeconomic status decline. Health Psychology, 33, 139-146. doi:10.1037/a0031661 | Detail

- , 2007: Moving beyond "special needs": A function-based framework for emergency management and planning. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 17, 230-237. doi:10.1177/10442073070170040601 | Detail

- , 2008: Building human resilience: The role of public health preparedness and response as an adaptation to climate change. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 508-516. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.022 | Detail

- , 2010: Alaskan wild berry resources and human health under the cloud of climate change. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 58, 3884-3900. doi:10.1021/jf902693r | Detail

- , 2014: Heat waves and health outcomes in Alabama (USA): The importance of heat wave definition. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122, 151–158. doi:10.1289/ehp.1307262 | Detail

- , 2007: Ten largest racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States based on Healthy People 2010 objectives. American Journal of Epidemiology, 166, 97-103. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm044 | Detail

- , 2013: Epidemiology of exertional heat illness among U.S. high school athletes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44, 8-14. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.058 | Detail

- , 2004: Ambient air pollution: Health hazards to children. Pediatrics, 114, 1699-1707. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2166 | Detail

- , 1997: Socioeconomic status and racial and ethnic differences in functional status associated with chronic diseases. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 805-810. doi:10.2105/AJPH.87.5.805 | Detail

- , 2010: Climate change, water resources and child health. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 95, 545-549. doi:10.1136/adc.2009.175307 | Detail

- , 2009: The direct impact of climate change on regional labor productivity. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 64, 217-227. doi:10.1080/19338240903352776 | Detail

- , 2009: Plasmodium vivax malaria among U.S. Forces Korea in the Republic of Korea, 1993-2007. Military Medicine, 174, 412-418. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-01-4608 | Detail

- , 2009: The 2006 California heat wave: Impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environmental Health Perspectives, 117, 61-67. doi:10.1289/ehp.11594 | Detail

- , 2005: An outbreak of malaria in US Army Rangers returning from Afghanistan. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 293, 212-216. doi:10.1001/jama.293.2.212 | Detail

- , 2008: Heat stress and public health: A critical review. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 41-55. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090843 | Detail

- , 2013: Minimization of heatwave morbidity and mortality. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44, 274-282. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.015 | Detail

- , 2004: Arctic indigenous peoples experience the nutrition transition with changing dietary patterns and obesity. The Journal of Nutrition, 134, 1447-1453. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Providing shelter to nursing home evacuees in disasters: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1288-1293. doi:10.2105/ajph.2006.107748 | Detail

- , 2009: Travelling and hunting in a changing Arctic: Assessing Inuit vulnerability to sea ice change in Igloolik, Nunavut. Climatic Change, 94, 363-397. doi:10.1007/s10584-008-9512-z | Detail

- , 2013: Health effects of coastal storms and flooding in urban areas: A review and vulnerability assessment. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2013, 1-13. doi:10.1155/2013/913064 | Detail

- , 2009: Neighborhood environments: Disparities in access to healthy foods. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36, 74-81.e10. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025 | Detail

- , 2010: Outdoor air pollutants and patient health. American Family Physician, 81, 175-180. URL | Detail

- , 2012: Vulnerability beyond stereotypes: Context and agency in hurricane risk communication. Weather, Climate, and Society, 4, 103-109. doi:10.1175/wcas-d-12-00015.1 | Detail

- , 2002: Hazardous air pollutants and asthma. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110 Suppl 4, 505-526. URL | Detail

- , 2009: Emergency preparedness for higher risk populations: Psychosocial considerations. Radiation Protection Dosimetry, 134, 207-214. doi:10.1093/rpd/ncp084 | Detail

- , 2009: Temperature mediated moose survival in northeastern Minnesota. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 73, 503-510. doi:10.2193/2008-265 | Detail

- , 2012: Harmful algal blooms along the North American west coast region: History, trends, causes, and impacts. Harmful Algae, 19, 133-159. doi:10.1016/j.hal.2012.06.009 | Detail

- , 2010: Surveillance for human West Nile virus disease - United States, 1999-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report - Surveillance Summaries, 59, 1-17. PMID: 20360671 | Detail

- , 2009: Extreme high temperatures and hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Epidemiology, 20, 738-746. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181ad5522 | Detail

- , 2008: Chronic exposure to ambient ozone and asthma hospital admissions among children. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116, 1725-1730. doi:10.1289/ehp.11184 | Detail

- , 2004: Rapid assessment of the needs and health status of older adults after Hurricane Charley--Charlotte, DeSoto, and Hardee Counties, Florida, August 27-31, 2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 53, 837-840. PMID: 15371964 | Detail

- , 2014: Hidden shift of the ionome of plants exposed to elevated CO2 depletes minerals at the base of human nutrition. eLife, 3, e02245. doi:10.7554/eLife.02245 | Detail

- , 2008: Climate change and extreme heat events. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 429-435. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.021 | Detail

- , 2009: Climate change and human health. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 120, 113-117. URL | Detail

- , 2014: Ch. 9: Human Health. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, , U.S. Global Change Research Program, 220-256. doi:10.7930/J0PN93H5 | Detail

- , 2013: Effects of heat stress on working populations when facing climate change. Industrial Health, 51, 3-15. doi:10.2486/indhealth.2012-0089 | Detail

- , 2013: The impacts of climate change on tribal traditional foods. Climatic Change, 120, 545-556. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0736-1 | Detail

- , 2008: Vulnerability to air pollution health effects. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 211, 326-336. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2007.06.005 | Detail

- , 2013: Fear of discovery among Latino immigrants presenting to the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 20, 155-161. doi:10.1111/acem.12079 | Detail

- , 2014: Assessing Health Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Guide for Health Departments. 24 pp., Climate and Health Technical Report Series, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. URL | Detail

- , 2012: Born Too Soon: The Global Action Report on Preterm Birth. 112 pp., World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. URL | Detail

- , 2007: Psychotropic drugs use and risk of heat-related hospitalisation. European Psychiatry, 22, 335-338. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.03.007 | Detail

- , 2013: Discharge-based QMRA for estimation of public health risks from exposure to stormwater-borne pathogens in recreational waters in the United States. Water Research, 47, 5282-5297. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2013.06.001 | Detail