Climate Change and Human Health

Human

Given that the impacts of climate change are projected to increase over the next century, certain existing health threats will intensify and new health threats may emerge. Connecting our understanding of how climate is changing with an understanding of how those changes may affect human health can inform decisions about mitigating (reducing) the amount of future climate change, suggest priorities for protecting public health, and help identify research needs.

Observed

Climate Change

The fact that the Earth has warmed over the last century is unequivocal. Multiple observations of air and ocean temperatures, sea level, and snow and ice have shown these changes to be unprecedented over decades to millennia. Human influence has been

the dominant cause of this observed warming.1 The 2014 U.S.

National Climate Assessment (2014

The concepts of climate and weather are often confused. Weather is the state of the atmosphere at any given time and place. Weather patterns vary greatly from year to year and from region to region. Familiar aspects of weather include temperature, precipitation, clouds, and wind that people experience throughout the course of a day. Severe weather conditions include hurricanes, tornadoes, blizzards, and droughts. Climate is the average weather conditions that persist over multiple decades or longer. While the weather can change in minutes or hours, identifying a change in climate has required observations over a time period of decades to centuries or longer. Climate change encompasses both increases and decreases in temperature as well as shifts in precipitation, changing risks of certain types of severe weather events, and changes to other features of the climate system.

Observed changes in climate and weather differ at local and regional scales (Figure 1.1). Some climate and weather changes already observed in the United States include:2, 3

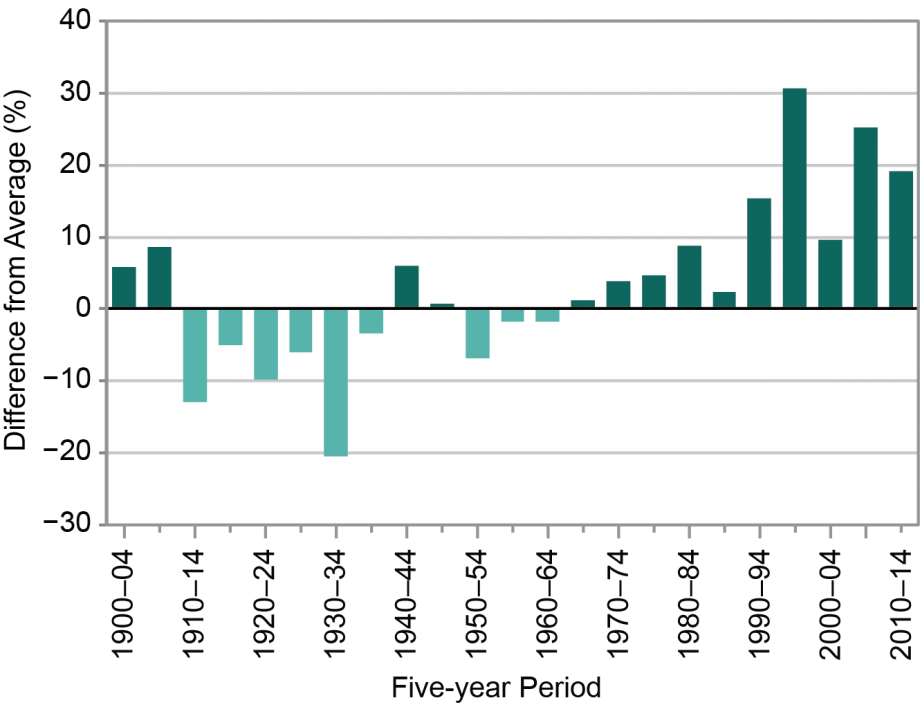

Figure 1.2: Change in Number of Extreme Precipitation Events

VIEW- U.S. average temperature has increased by 1.3°F to 1.9°F since recordkeeping began in 1895; most of this increase has occurred since about 1970. The first decade of the 2000s (2000–2009) was the warmest on record throughout the United States.

- Average U.S. precipitation has increased since 1900, but some areas have experienced increases greater than the national average, and some areas have experienced decreases.

- Heavy downpours are increasing nationally, especially over the last three to five decades. The largest increases are in the Midwest and Northeast, where floods have also been increasing. Figure 1.2 shows how the annual number of heavy downpours, defined as extreme two-day precipitation events, for the contiguous United States has increased, particularly between the 1950s and the 2000s.

-

Drought has increased in the West. Over the last decade, the Southwest has experienced the most persistent droughts since record keeping began in 1895.4 Changes in precipitation and runoff, combined with changes in consumption and withdrawal, have reduced surface and groundwater supplies in many areas. - There have been changes in some other types of extreme weather events over the last several decades. Heat waves have become more frequent and intense, especially in the West. Cold waves have become less frequent and intense across the nation.

- The intensity, frequency, and duration of North Atlantic hurricanes, as well as the frequency of the strongest (category 4 and 5) hurricanes, have all increased since the early 1980s. The relative contributions of human and natural causes to these increases remain uncertain.

Projected Climate Change

Projections of future climate conditions are based on results from climate models—sophisticated computer programs that simulate the behavior of the Earth’s climate system. These climate models are used to project how the climate system is expected to

change under different possible scenarios. These scenarios describe future changes in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations,

Figure 1.3: Projected Changes in Temperature and Precipitation by Mid-Century

Interact with the Figure Below

Some of the projected changes in climate in the United States as described in the 2014 NCA are listed below:2, 3

- Temperatures in the United States are expected to continue to rise. This temperature rise has not been, and will not be, uniform across the country or over time (Figure 1.3).

- Increases are also projected for extreme temperature conditions. The temperature of both the hottest day and coldest night of the year are projected to increase (Figure 1.4).

- More winter and spring precipitation is projected for the northern United States, and less for the Southwest, over this century (Figure 1.3).

- Increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events are projected for all U.S. areas (Figure 1.4).

- Short-term (seasonal or shorter) droughts are expected to intensify in most U.S. regions. Longer-term droughts are expected to intensify in large areas of the Southwest, the southern Great Plains, and the Southeast. Trends in reduced surface and groundwater supplies in many areas are expected to continue, increasing the likelihood of water shortages for many uses.

- Heat waves are projected to become more intense, and cold waves less intense, everywhere in the United States.

- Hurricane-associated storm intensity and rainfall rates are projected to increase as the climate continues to warm.

Figure 1.4: Projected Changes in the Hottest/Coldest and Wettest/Driest Day of the Year

Interact with the Figure Below

The influences of

A useful approach to understand how climate change affects health is to consider specific

Whether or not a person is exposed to a health threat or suffers illness or other adverse health outcomes from that exposure depends on a complex set of

- Exposure is contact between a person and one or more biological, psychosocial, chemical, or physical stressors, including stressors affected by climate change. Contact may occur in a single instance or repeatedly over time, and may occur in one location or over a wider geographic area.

-

Sensitivity is the degree to which people or communities are affected, either adversely or beneficially, by

climate variability or change. -

Adaptive capacity is the ability of communities, institutions, or people to adjust to potential hazards, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences. A related term, resilience, is the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events.

(definitions adapted from

Vulnerability, and the three components of vulnerability, are factors that operate at multiple levels, from the individual and community to the country level, and affect all people to some degree.9 For an individual, these factors include human behavioral choices and the degree to which that person is vulnerable based on his or her level of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Vulnerability is also influenced by

At a larger community or societal scale, health outcomes are strongly influenced by adaptive capacity factors, including those related to the natural and built environments (for example, the state of

The three components of vulnerability (exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity) are associated with social and

Figure 1.5: Climate Change and Health

We are already experiencing changes in the frequency, severity, and even the location of some weather and climate phenomena, including extreme temperatures, heavy rains and droughts, and some other kinds of severe weather, and these changes are projected

to continue. This means that areas already experiencing health-threatening weather and climate phenomena, such as severe heat or hurricanes, are likely to experience worsening impacts, such as even higher temperatures and increased

storm intensity, rainfall rates, and

Climate change can therefore affect human health in two main ways: first, by changing the severity or frequency of health problems that are already affected by climate or weather factors; and second, by creating unprecedented or unanticipated health problems or health threats in places where they have not previously occurred.

In order to understand how

Demographic and Socioeconomic Trends

The United States is in the midst of several significant demographic changes: the population is aging, growing in number, becoming more ethnically diverse, and demonstrating greater disparities between the wealthy and the poor. Immigration is having a major influence on both the size and age distribution of the population.15 Each of these demographic trends has implications for climate change related human health impacts (see Ch. 9: Populations of Concern). Some of these trends and projections are summarized below:

Trends in population growth

- The total U.S. population has more than doubled since 1950, from 151,325,798 persons in 1950 to 308,745,538 in 2010.16

- The Census Bureau projects that the U.S. population will grow to almost 400 million by 2050 (from estimates of about 320 million in 2014).17

Trends in the elderly population

- The nation’s older adult population (ages 65 and older) will nearly double in number from 2015 through 2050, from approximately 48 million to 88 million.18 Of those 88 million older adults, a little under 19 million will be 85 years of age and older.19

Trends in racial and ethnic diversity

- As the United States becomes more diverse, the aggregate minority population is projected to become the majority by 2042.18 The non-Hispanic or non-Latino White population will increase, but more slowly than other racial groups. Non-Hispanic Whites are projected to become a minority by 2050.20

- Projections for 2050 suggest that nearly 19% of the population will be immigrants, compared with 12% in 2005.20

- The Hispanic population is projected to nearly double from 12.5% of the U.S. population in 2000 to 24.6% in 2050.21

Trends in economic disparity

- Income inequality rose and then stabilized during the last 30 years, and is projected to resume rising over the next 20 years, though at a somewhat slower overall rate that declines to near zero by 2035.22 For example, the Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, is estimated to have risen by 18% between 1984 and 2000, and is projected to rise by an additional 17% for all workers between 2009 and 2035.22

- America’s communities of color have disproportionately higher poverty rates and lower income levels. While racial disparities in household wealth were higher in the late 1980s than now, trends in more recent years have been toward greater inequality. The ratio of the median net household worth of White, non-Hispanic versus non-White or Hispanic households increased from 6.0 to 7.8 between 2007 and 2013.23 In 2009, 25.8% of non-Hispanic Blacks and 25.3% of Hispanics had incomes below the poverty level as compared to 9.4% of non-Hispanic Whites and 12.5% of Asian Americans.24 In 2014, the median income level for a non-Hispanic Black household was approximately $35,000, $25,000 lower than a non-Hispanic White household.25

Population growth and migration in the United States may place more people at

Trends in Health Status

Storm-damaged home after Hurricane Sandy

© iStockPhoto. com/Aneese

As a nation, trends in the population’s health are mixed. Some major indicators of health, such as life expectancy, are consistently improving, while others, such as rate and number of

Climate change impacts to human health will act on top of these underlying trends. Some of these underlying health conditions can increase

Examples of health indicators that have been improving between 2000 and 2013 include the following:

- Life expectancy at birth increased from 76.8 to 78.8 years.30

- Death rates per 100,000 people from heart disease and cancer decreased from 257.6 to 169.8 and from 199.6 to 163.2, respectively.30

- The percent of people over age 18 who say they smoke decreased from 23.2% to 17.8%.30

© Monkey Business Images/Corbis

At the same time, some health trends related to the prevalence of

- The percentage of adult (18 years and older) Americans describing their health as “poor or fair” increased from 8.9% in 2000 to 10.3% in 2012.30

- Prevalence of physician-diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 20 and over increased from 5.2% in 1988-1994 to 8.4% in 2009-2012.30

- The prevalence of obesity among adults (aged 20–74) increased by almost three-fold from 1960–1962 (13.4% of adults classified as obese) to 2009–2010 (36.1% of adults classified as obese).31

- In the past 30 years, obesity has more than doubled in children and quadrupled in adolescents in the United States. The percentage of children aged 6–11 who were obese increased from 7% in 1980 to nearly 18% in 2012. Similarly, the percentage of adolescents aged 12–19 years who were obese increased from 5% to nearly 21% over the same period. In 2012, approximately one-third of American children and adolescents were overweight or obese.32

Table 1.1 shows some examples of underlying health conditions that are associated with increased vulnerability to health effects from climate change related exposures (see Ch. 9: Populations of Concern for more details) and provides information on current status and future trends.

Health status is often associated with demographics and socioeconomic status. Changes in the overall size of the population, racial and ethnic composition, and age distribution affect the health status of the population. Poverty, educational attainment, access to care, and discrimination all contribute to disparities in the incidence and prevalence of a variety of medical conditions (see Ch. 9: Populations of Concern). Some examples of these interactions include:

Older Adults. In 2013, the percentage of adults age 75 and older described as persons in fair or poor health totaled 27.6%, as compared to 6.2% for adults age 18 to 44.30Among adults age 65 and older, the number in nursing homes or other residential care facilities totaled 1.8 million in 2012, with more than 1 million utilizing home health care.33

© Stephen Welstead/LWA/ Corbis

Children. Approximately 9.0% of children in the United States have asthma. Between 2011 and 2013, rates for Black (15.3%) and Hispanic (8.6%) children were higher than the rate for White (7.8%) children.30 Rates of asthma were also higher in poor children who live below 100% of the poverty level (12.4%).30

Non-Hispanic Blacks. In 2014, the percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks of all ages who were described as persons in fair or poor health totaled 14.3% as compared to 8.7% for Whites. Health risk factors for this population include

high rates of smoking, obesity, and

Hispanics. The percentage of Hispanics of all ages who were described as persons in fair or poor health totaled 12.7% in 2014. Health disparities for Hispanics include moderately higher rates of smoking in adults, low birth weights, and infant deaths.30

The impacts of climate change may worsen these health disparities by exacerbating some of the underlying conditions they create. For example, disparities in life expectancy may be exacerbated by the effects of climate change related heat and air pollution on minority populations that have higher rates of hypertension, smoking, and diabetes. Conversely, public health measures that reduce disparities and overall rates of illness in populations would lessen vulnerability to worsening of health status from climate change effects.

Table 1.1: Current estimates and future trends in chronic health conditions that interact with the health risks associated with climate change

Click on a table row for more information.

|

|

Current Estimates | Future Trends |

Possible Influences of

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE | Approximately 5 million Americans over 65 had Alzheimer's disease in 2013.34 |

|

Persons with

|

|

|

Average asthma prevalence in the U.S. was higher in children (9% in 2014)30 than in adults (7% in 2013).35 Since the 1980s, asthma prevalence increased, but rates of asthma deaths and hospital admissions declined.36, 37 |

Stable

|

Asthma is exacerbated by changes in pollen season and allergenicity and in exposures to air pollutants affected by changes in temperature, humidity, and wind.29 |

|

|

In 2012, approximately 6.3% of adults had COPD. Deaths from chronic lung diseases increased by 50% from 1980 to 2010.38, 39 |

Chronic

|

COPD patients are more sensitive than the general population to changes in ambient air quality associated with climate change. |

|

|

In 2012, approximately 9% of the total U.S. population had diabetes. Approximately 18,400 people younger than age 20 were newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in 2008–2009; an additional 5,000 were diagnosed with type 2. 40 | New diabetes cases are projected to increase from about 8 cases per 1,000 in 2008 to about 15 per 1,000 in 2050. If recent increases continue, prevalence is projected to increase to 33% of Americans by 2050. 41 |

Diabetes increases

|

|

|

Cardiovascular disease (

|

By 2030, approximately 41% of the U.S. population is projected to have some form of CVD.43 | Cardiovascular disease increases sensitivity to heat stress. |

| MENTAL ILLNESS |

|

By 2050, the total number of U.S. adults with depressive disorder is projected to increase by 35%, from 33.9 million to 45.8 million, with those over age 65 having a 117% increase. 44 |

Mental illness may impair responses to

|

|

|

In 2009–2010, approximately 35% of American adults were obese.32 In 2012, approximately 32% of youth (aged 2–19) were overweight or obese.46, 47 | By 2030, 51% of the U.S. population is expected to be obese. Projections suggest a 33% increase in obesity and a 130% increase in severe obesity.48 | Obesity increases sensitivity to high ambient temperatures. |

|

|

Approximately 18.7% of the U.S. population has a disability. In 2010, the percent of American adults with a disability was approximately 16.6% for those age 21–64 and 49.8% for persons 65 and older. 49 | The number of older adults with activity limitations is expected to grow from 22 million in 2005 to 38 million in 2030.50 | Persons with disabilities may find it hard to respond when evacuation is required and when there is no available means of transportation or easy exit from residences. |

For some changes in exposures to

The ability to quantify many types of health impacts is dependent on the availability of data on the baseline

Information on trends in underlying health or background rates of health impacts is summarized in Section 1.3, “Our Changing Health.” Data on the incidence and prevalence of health

conditions are obtained through a complicated system of state- and city-level

Characterizing certain types of climate change related exposures can be a challenge. Exposures can consist of temperature changes and other

Modeling Approaches Used in this Report

Four chapters within this assessment—Ch. 2: Temperature-Related Death and Illness, Ch. 3: Air Quality Impacts, Ch. 5: Vector-Borne Diseases, and

Ch. 6: Water-Related Illness—include new peer-reviewed, quantitative analyses based on modeling. The analyses highlighted in these chapters mainly relied on climate model output from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project

Phase 5 (CMIP5). Due to limited data availability and computational resources, the studies highlighted in the four chapters analyzed only a subset of the full CMIP5 dataset, with most of the studies including at least one analysis

based on RCP6.0, an upper midrange greenhouse gas concentration pathway, to facilitate comparisons across chapters. For example, the air quality analysis examined results from two different RCPs, with a different climate model

used for each, while the waterborne analyses examined results from 21 of the CMIP5 models for a single

Adverse health effects attributed to climate change can have many economic and social consequences, including direct medical costs, work loss, increased care giving, and other limitations on everyday activities. Though economic impacts are a crucial component to understanding risk from climate change, and may have important direct and secondary impacts on human health and well-being by reducing resources available for other preventative health measures, economic valuation of the health impacts was not reported in this assessment.

Uncertainty in Health Impact Assessments

Figure 1.6 illustrates different sources of uncertainty along the exposure pathway.

Figure 1.6: Sources of Uncertainty

Two of the key uncertainties in projecting future global temperatures are 1) uncertainty about future concentrations of

Uncertainty in current and future estimates of health or

The factors related to uncertainty in exposure–response functions are similar to those for the projections of health or socioeconomic status. Estimates are more uncertain for smaller subpopulations, less-prevalent health conditions, and smaller geographic areas. Because these estimates are based on observations of real populations, their validity when applied to populations in the future is more uncertain the further into the future the application occurs. Uncertainty in the estimates of the exposure–outcome relationship also comes from factors related to the scientific quality of relevant studies, including appropriateness of methods, source of data, and size of study populations. Expert judgment is used to evaluate the validity of an individual study as well as the collected group of relevant studies in assessing uncertainty in estimates of exposure–outcome relationships.

Approach to Reporting Uncertainty in Key Findings

Despite the sources of uncertainty described above, the current state of the science allows an examination of the likely direction of and trends in the health impacts of climate change. Over the past ten years, the models used for climate and health assessments have become more useful and more accurate (for example, Melillo et al. 2014).6, 53,54 This assessment builds on that improved capability. A more detailed discussion of the approaches to addressing uncertainty from the various sources can be found in the Guide to the Report and Appendix 1: Technical Support Document.

Two kinds of language are used when describing the uncertainty associated with specific statements in this report: confidence language and likelihood language (see below). Confidence in the validity of a finding is expressed qualitatively and is based on the type, amount, quality, strength, and consistency of evidence and the degree of expert agreement on the finding. Likelihood, or the projected probability of an impact occurring, is based on quantitative estimates or measures of uncertainty expressed probabilistically (in other words, based on statistical analysis of observations or model results, or on expert judgment). Whether a Key Finding has a confidence level associated with it or, where findings can be quantified, both a confidence and likelihood level associated with it, involves the expert assessment and consensus of the chapter author teams.

Likelihood and Confidence Level

Likelihood

|

Very Likely ≥9 in 10 |

Likely ≥2 in 3 |

As Likely as Not ≈ 1 in 2 |

Unlikely ≤ 1 in 3 |

Very Unlikely ≤1 in 10 |

Confidence Level

References

- , 2012: Trends in Asthma Prevalence, Health Care Use, and Mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief. No. 94, May 2012. Array, 8 pp., National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. URL | Detail

- 2014: 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances: SCF Chartbook. URL | Detail

- , 2013: The effectiveness of public health interventions to reduce the health impact of climate change: A systematic review of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE, 8, e62041. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062041 | Detail

- , 2012: Americans With Disabilities: 2010. 23 pp., U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- cited 2014: National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- cited 2015: Lyme Disease Surveillance and Available Data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL | Detail

- , 2014: Ch. 11: Urban Systems, Infrastructure, and Vulnerability. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, , U.S. Global Change Research Program, 282-296. doi:10.7930/J0F769GR | Detail

- , 2015: Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Community-based adaptation to the health impacts of climate change. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 501-507. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.018 | Detail

- 2012: Climate Change Indicators in the United States, 2nd Edition. 84 pp., U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- , 2012: Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Extreme Obesity Among Adults: United States, Trends 1960-1962 through 2009-2010. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. URL | Detail

- , 2010: Poverty in the United States, 2009. Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- , 2006: Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Global Environmental Change, 16, 293-303. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004 | Detail

- , 2013: Long-Term Care Services in the United States: 2013 Overview. 107 pp., National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. URL | Detail

- , 2008: Population projection of US adults with lifetime experience of depressive disorder by age and sex from year 2005 to 2050. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 1266-1270. doi:10.1002/gps.2061 | Detail

- , 2012: Integrating climate change adaptation into public health practice: Using adaptive management to increase adaptive capacity and build resilience. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120, 171-179. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103515 | Detail

- 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1535 pp., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324 | Detail

- 2014: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1132 pp., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY. URL | Detail

- , 2014: CDC National Health Report: Leading Causes of Morbidity and Mortality and Associated Behavioral Risk and Protective Factors - United States, 2005-2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report - Supplements, 63, 3-27. PMID: 25356673 | Detail

- , 2012: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults - United States, 2011. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61, 938-943. URL | Detail

- , 2014: Ch. 9: Human Health. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, , U.S. Global Change Research Program, 220-256. doi:10.7930/J0PN93H5 | Detail

- , 2014: Appendix 5: Scenarios and Models. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, U.S. Global Change Research Program, 821-825. doi:10.7930/J0B85625 | Detail

- , 2014: Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, 841 pp. doi:10.7930/J0Z31WJ2 | Detail

- , 2012: National Surveillance of Asthma: United States, 2001-2010. National Center for Health Statistics. URL | Detail

- , 2014: Ch. 25: Coastal Zone Development and Ecosystems. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, , U.S. Global Change Research Program, 579-618. doi:10.7930/J0MS3QNW | Detail

- 2015: Health, United States, 2014: With Special Feature on Adults Aged 55-64. 473 pp., National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD. URL | Detail

- 2006: Hispanics and the Future of America. , National Research Council. The National Academies Press, 502 pp. URL | Detail

- 2012: Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. National Academies Press, 244 pp. | Detail

- , 2014: Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 311, 806-814. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.732 | Detail

- , 2008: U.S. Population Projections: 2005-2050. 49 pp., Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- , 2012: Variation in estimated ozone-related health impacts of climate change due to modeling choices and assumptions. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120, 1559-1564. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104271 | Detail

- , 2013: Modeling Individual Earnings in CBO’s Long-term Microsimulation Model. 28 pp., Congressional Budget Office, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- , 2011: The Changing Demographic Profile of the United States. 32 pp., Congressional Research Service. URL | Detail

- , 2006: Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16, 282-292. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.03.008 | Detail

- , 2015: Regional Surface Climate Conditions in CMIP3 and CMIP5 for the United States: Differences, Similarities, and Implications for the U.S. National Climate Assessment. Array, 111 pp., National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. doi:10.7289/V5RB72KG | Detail

- , 2007: Climate and human health: Synthesizing environmental complexity and uncertainty. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 21, 601-613. doi:10.1007/s00477-007-0142-1 | Detail

- cited 2010: U.S. Census 2010: Resident Population Data. U.S. Department of Commerce. URL | Detail

- 2010: The Next Four Decades, The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050, Population Estimates and Projections. Array, 16 pp., U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Division, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. URL | Detail

- cited 2014: 2014 National Population Projections: Summary Tables. Table 9. Projections of the Population by Sex and Age for the United States: 2015 to 2060. U.S. Department of Commerce. URL | Detail

- cited 2014: 2014 National Population Projections: Summary Tables. Table 1. Projections of the Population and Components of Change for the United States: 2015 to 2060 (NP2014-T1). U.S. Department of Commerce. URL | Detail

- , 2014: Ch. 2: Our Changing Climate. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, , U.S. Global Change Research Program, 19-67. doi:10.7930/J0KW5CXT | Detail

- , 2014: Appendix 3: Climate Science Supplement. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, , U.S. Global Change Research Program, 735-789. doi:10.7930/J0KS6PHH | Detail